A look at the factors driving Greece's trade deficit wider. Is this time any different?

(This post was originally published on Jan 4th 2023)

Saying that the past 3 years have been eventful would be a good candidate for understatement of the century. In the midst of (and also because of) this flurry of once in a century type of events Greece’s trade deficit has, yet again, widened significantly. Greece is certainly not the only economy to experience something of the sort but given our recent past it should come as no surprise that brutal memories have been awakened and muscle memory has kicked in. In this post we’ll try to untangle the drivers behind that new bout of trade deficit widening and try to, clumsily, quantify each one’s contribution.

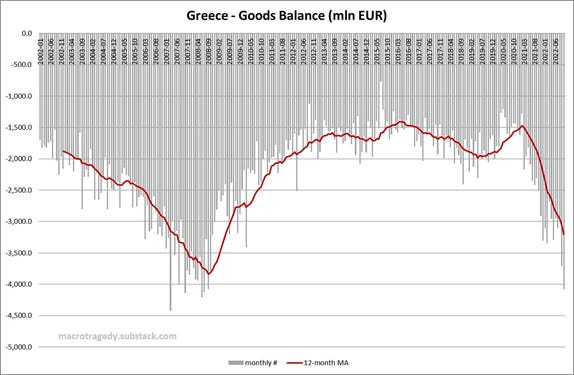

First of all, we need to clarify that by trade deficit we mean the external goods balance and just that.

Being pedantically exact, we also have to say that Greece’s trade deficit hasn’t just widened. In October 2022 it came in a hair’s breadth away from March’s 2007 lows.

source: Eurostat, own calculations

The factors driving this though are not entirely the same with those that did the driving back in the pre-GFC period.

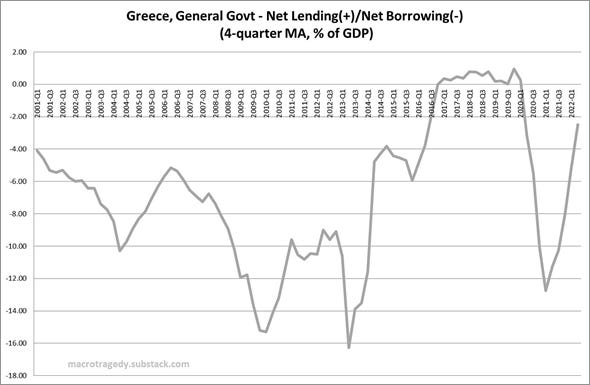

The one factor also in play back then is expansionary fiscal policies. Policies like that stoke domestic demand and in an economy that’s running a structural trade deficit this means that part of the increased demand will be translated in increased imports.

In my humble opinion, this latest bout of fiscal expansion can be broken down in two distinct periods. The first one involved the bundle of measures enacted to address the COVID emergency and was definitely of the counter-cyclical variety as it sought to cushion the blow on the economy in general but also in one of the main pillars of the country’s economic model, the hospitality sector. The second one involves the measures put it place in an effort to contain the adverse effects of the broad inflationary surge that is underway, on households and businesses and is not countercyclical per se (at least for the time being) but it falls under the umbrella of crisis-mitigating measures.

As the chart below makes glaringly obvious the scale of this latest round of fiscal loosening is light years away from the fiscal free-for-all of the 00s so the notion that this alone caused the deficit to widen by that much seems highly unlikely. Also, the credit boom that took place back then is absent now.

source: Eurostat, own calculations

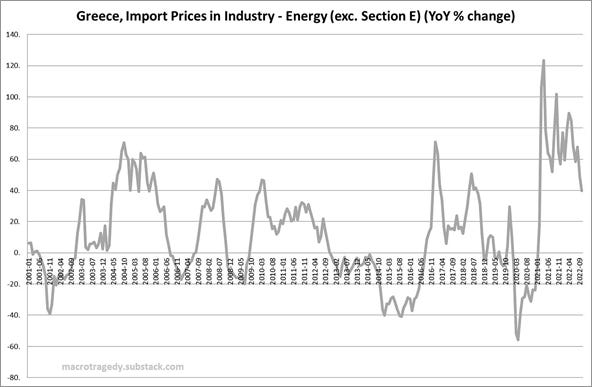

The other major factor at work is none other than the broad and protracted inflationary pressures that are currently plaguing the world economy. The fact that these were kick-started by a huge spike in energy prices means that this is nothing else but a negative terms-of-trade (the ratio of export prices and import prices) shock for a commodity-importing economy like Greece.

To showcase the exacerbated price movements impacting Greece’s imports, the Producer Price Index for Industry for the whole of the Euro Area will be used and the Energy component of the Import Price Index for Greece (since Greece’s Energy imports don’t, for the most part, come from the Euro Area). We have to clarify that Energy hereby includes Coal & Lignite, Crude Petroleum & Natural Gas, Coke & Refined Petroleum Products and Electricity.

As you can see, the YoY increase of the Energy Import Price Index reached unprecedented levels back in early-2021 and its levels in Oct could still stack up against previous waves’ highs.

source: Eurostat

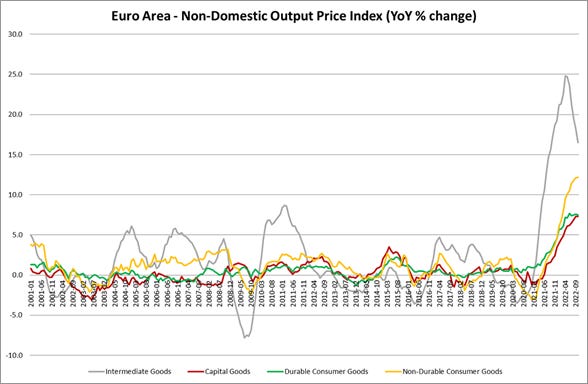

Something else that differentiates this inflationary surge from others is that Export Price changes for all major industrial groupings (MIGs) cleared their previous highs by a country mile something that is not common as in previous such episodes, with the exception of Intermediate Goods, prices for other MIGs usually were not that sensitive to changes in energy prices.

source: Eurostat

Since such intense price pressures distort the picture that nominal data paint, in circumstances like these one would normally opt to look at data expressed in real terms. The problem when it comes to international trade is that such data are very hard to come by. And given that I’m not a big fan of deflating nominal time-series on a DIY basis, the only solution I could come up with is using the national accounts data for goods imports and exports. Then by subtracting the former from the latter one can obtain the trade balance in real terms.

source: Eurostat

So, when expressed in real terms, Greece's trade deficit is not only significantly narrower but it also hasn’t widened by all that much in 2022.

Now it’s time to try and do what was advertised in the opening paragraph, i.e. try to quantify each factor’s contribution. Choosing 2020Q2 as our point of reference, we see that between 2020Q2 and 2022Q3 the trade balance widened by 5.787 bln EUR in nominal terms while in real terms it widened by 3.162 bln EUR. Since the widening in real terms is devoid of the impact of rising prices one could assume that this equals the part that can be attributed to increased demand, roughly 54.6% of total. The rest can be attributed to the effect of the terms-of-trade shock and would be roughly equal to 45.4% of total.

To sum this up, Greece's trade deficit reaching late-2008 levels again wasn’t due to a case of exorbitant excess this time around but due to events largely outside of the country's policymakers control as well as the economy's, sadly ever-present, structural characteristics. Sure, the fiscal policy response could have been better targeted at times but, by and large, in most countries cost-benefit considerations tipped the policy scales in a direction not wholly different from the one chosen in Greece’s case.